Chapter 5: The March

- Colonial-NewYorker

- Aug 20

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 20

V

The March

“Mr. Livingston!” cried a voice from within the throng, and out walked a man unfamiliar to George. He wore a simple brown coat, a cocked hat, and walked with a cane as gentlemen were accustomed to doing, and this was altogether normal, yet the man's face was odd and caused George to pause and rudely stare. It was a face of middle years, stretched and scarred with wear, and whipped and lashed by the briny ocean, and his grey eyes, in which the faintest remnant of blue glowed in the torchlight, seemed oddly tempestuous. “Mr. Sears. I'm not surprised to see you here.” Robert said, clasping the man in a warm embrace, to whom the man smiled, saying, “Look at you, your father’s son! This is a momentous time, Mr. Livingston, for we are prepared to strike a decisive blow! The governor cannot help but hear our cries conjoined in such great numbers, and I am proud to witness the occasion.” Upon noticing George and John, he asked, “and who are your companions?”

Robert pulled George close and answered, “George Van Den Bos, and John Jay. Both studious Sons of Liberty from King's College,” at which they both bowed in the requisite greetings of the time, and having returned the favor, he said, “Not Peter's son?” “Yes sir. The very same.” “Good lad, and Van Den Bos, a most unfamiliar name. I’m always interested in unfamiliar names,” after which he briefly peered into George's eyes, then said, “I think it's prudent that I tell you three, such upstanding gentlemen from King's College, to be vigilant tonight, lest the crowd get too excited. If the crowd turns mob and violence breaks lose, try at all cost to pacify whom you may, for too much depends upon our demonstrations. We must exude a sense of legal legitimacy in our arguments; we will not if the rabble throws a fuss and begins defacing property like they did in Boston.”

“You needn't worry Sir, for whilst Parliament is indeed misled, legal sobriety is a requisite quality in all protest. You have our word,” said George in his high-minded rhetoric, and smiling, Mr. Sears said, “Good man! Keep close to this one Mr. Livingston, now I must be off to speak with other friends of liberty, Mr. Jay, Mr. Van Den Bos,” and tipping his cocked hat, he stalked back into the bustling crowd. After which John snorted, struggling to restrain a boisterous laugh. George gave a bewildered stare at his friend for the inopportune (and perhaps inappropriate) laughter and said, “What’s the matter?” John, finally able to half-compose himself, said, “Didn’t Rob say that we would go down to the governor tonight?” and then, barely able to contain his laughter anymore, he spurted out, “perhaps tonight you could really find a woman, George!” at this he laughed so hard his face turned a shade purple, and Robert along with him.

George blushed and said in the driest voice that he could force, “Amusing, John,” and he would have left it at that had his mouth more government, for he sadly professed an apology, “Indeed, Professor Cooper made a point of advice that I abandon any pursuit of marriage, until a time most agreeable to the profession of law. ‘Watch the ladies' said he, 'a woman brings both warmth and complacency, and the law requires your constant devotion…'” but before George could finish John said, “George, George, my friend, you are much too stiff...” but Robert interjected, “No, John, George is right. The application of a man who aims to be a lawyer must be...” “Perpetual?” said George, “Eternal?” added John in the very same breath. “No, no... 'it must be incessant'. I read of it in the Gazette, 'twas in an epistle from a retired barrister in New Hampshire. No better advice has ever graced my ears; 'his attention to his books must be constant' he finished.” “Aye, grand advice.” said George in agreement. Such lighthearted talk warmed the sober air.

George looked to his right as they followed the crowd down Broadway (for indeed his curiosity, and his inkling of civic duty, implored that he observe this demonstration) and there he saw the towering edifice that was St. Paul’s Chapel. The famous church was still in construction in those days, and its towering steeple, carved in elegant brickwork in the most modern and Georgian fashion, sat encased in woodworks. Nonetheless, a bright ray of light shone out from its frontal window, a staggering multi-paned glass portal stained baby blue, deep into the gloom of night. The light was broken into quarters by four Corinthian columns guarding the facade, and this holy-glow reminded George of the Tetragrammaton, which he once saw in flowing Hebrew calligraphy upon an old book of Isaiah. New York is the edifice of mankind, thought George, as he stared at the progress of carpenters, brick masons, and artisans. As he stared into the crowd that surrounded him, though he felt unease at the concept of extra-legal protest, he added, and we are the architects of liberty. He heard a dog's bark sound from afar.

After a moment of walking, George asked, “So, this Sears fellow, what of him? Is he the orchestrator of this demonstration?” “He's a leader of the Sons of Liberty in the city.” John said, “He's an old jack tar, from the private service I think, turned merchant and city organizer. Indeed, with the odd fellow here, I think we're in for a curious commotion, whether he managed this affair or not,” and again after a moment's silence, George said, a bothered look upon his face as he stared off into the night, “It's odd.” “Odd?” asked Robert. “Odd.” he repeated, “As a child, I dreamt of nothing more than joining the body politic, a loyal Englishman. My father inculcated in me a love of our mother country. Yet here I stand,” and feel conflicted, he thought to himself. “In principle” he added, “I stand with Sears and these fellows. For indeed it is a most noxious tax. Yet, still I feel...being here now...” “George,” Robert gently said, “We were raised upon the same yarns. If virtuous men had not stood athwart the juntoes of wicked kings and noxious legislation, and of all the pretenders and Jacobites, what then would be our English government? If we had not invited William of Orange, would there have been a charter of our rights? This is where we ought to be, my friend, the very time and place,” and George felt momentarily reassured, taking the next step determined with his co-patriots.

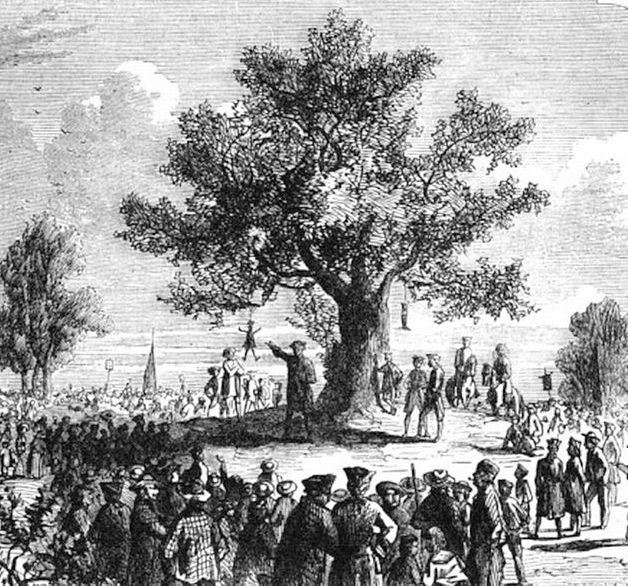

As they closed in upon the Battery, the salubrious sea breeze wafted in and purified the normal odor of horse and refuse, leaving the air crisp and fresh. The faint beacon-fires of the Fort, still a way down the Broadway, mingled in the mirage of illuminated windows and lantern-light from the porches of the many houses lining the dirty street. George shivered as the ocean air channeled up the road and he struggled to keep on his hat and powdered wig. The men were silent as they approached the Bowling Green and upon the view of the Fort, which enclosed the governor’s mansion, in which, presumably, were the detested stamps, George felt an icy stab of fear in his belly. The many cannon upon the battlement, which in normal times were pointed water-ward in guard of the harbor, were now pointing down upon the crowd, their menacing ports scowling blackness, their flints faint-pink ember warnings. George felt afraid, and indeed an unheard whisper could be felt to reverberate among the crowd, for Ire, the mother of Madness, began to sing her flaming song.

Warning: The Yellow Cardinal contains adult themes that may not be suitable for all audiences under the age of 18. Some chapters may contain descriptions of graphic scenarios including but not limited to: suggestive materials, violence, 18th century racism and slavery, sexism, etc. Read with caution and/or parental permission.

Comments