Chapter 3: To Arms! To Arms!

- Colonial-NewYorker

- Aug 19

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 20

III

To Arms! To Arms!

George pushed the red digest onto the shelf from which it came, and stood back, marveling at the tight and neat ranks of ribbed spines, some of leather, some velum, some inked, and some spare few of recycled leaf of monk-writ (one vertebra sporting clear Carolingian Miniscule: vexilla regis prodeū). He would often meditate upon the grand apothecary that now lay before him, for there seemed to be every species of book at King's College: titles from France, Italy, the Low Countries, from England of course, and from the Colonies themselves, though all acknowledged that these were inferior prints in every way. Indeed, rumor had it that Professor Cooper locked away incunables in some hidden grove in the college, and perhaps a few University of Paris manuscript bibles! Upon his arrival in the City of New York, George felt giddy at the thought of having free access to them all, tapping into the pulse of civilized society, into the beryl lethe of intellectual history. He would spend all his evenings after lecture sequestered on the third floor, his only company the famed interlocutors of poetry, history, and philosophy that filled those learned pages, filling out commonplace after commonplace with their wisdom and sententiae, signed with the choice penname Philanthropos. That is, until he befriended Robert and John, which, though their affection was first born of pity and mere circumstance, it soon blossomed into a flower of love and fraternity, the natural course of empathetic hearts.

As he closed and locked the glass door to the bookshelf, George felt a hand on his shoulder and, looking back, saw Robert, who said, “I believe it's been two weeks now since you began the Institutes, and I haven't seen you once take your nose out of it.” John, across the room, pulling tight an overcoat, interjected, “What of it, Rob? Nothing as bad as preparing for the bar. I think George is well positioned to surpass all of us.” At which George smiled, saying “It's not that I mean to supersede you, for I may never, wanting a fortune. Could ever I expect to do so with you Livingstons and DeLanceys pulling the strings of the city judges and bailiffs? Truly, post-partum you are legal ventriloquists, and I am but a farmer's son.” At this John burst out in laughter, and Robert himself could not help but smile at George's raging wit, “On second thought, I think John is right, do study on, my friend.”

After dousing the fire, and stopping all the candles, they fastened their coats and cocked hats, and walked down the stairs out into the yard of the college. King's College was well insulated from the boisterous city, as it was entirely cloistered and surrounded by a large rustic courtyard fit for scholars to pace about and masticate the words of their blackletter books in the springtime. George looked upon the pastoral scene and felt the November air reverberating with a chill born out from October, and he noticed in the dim moonlight that the lawn was glazed white with hoarfrost; pale ice crowned the rusty leaves, the remnant of autumn fluttering in muted boughs. Robert began “I fancy some aliment, what say you?” and indeed, their stomachs empty and their minds full, they all felt it worth stopping by a tavern to eat and be merry before retiring for the evening. Thus, they began out onto the dark streets of York City and closed the noisy gate to King's College.

Immediately beyond the safety of the college yard, one entered the “Holy Ground”, and be not beguiled dear reader, make sure to understand this name in a most perverse sense, morality be damned. The ‘Holy Ground’ was so named, ironically, for the many prostitutes who were its inhabitants and the many lusty men who wandered here among the scarlet lanes to indulge their many vices and carnal appetites. The grounds which housed these infamous tenants were owned by the parish of Trinity Church, and it can be assumed, like ‘Mount Whoredom’ in puritan Boston, remembered so fondly by a cheeky British cartographer, that all men of God ignored the rampant disregard for ecclesiastical law within its boundaries. George had marveled at his first sight of women in the scantly lit streets bent in all assortments of positions uttering sighs and groans. He had even once seen a woman leaning on a door naked, her wan breasts illuminated by the lantern light spilling from the steps, which, to his shame, caused his face to redden and his heart to race. However, Myles Cooper made it abundantly clear: the illicit activities of the ‘Holy Ground’ were strictly forbidden to the students at King's College, and so when leaving school, the boys tended to make all haste for better quarters.

“It's unusually quiet tonight” George remarked as they walked eastward down Murray Street, “Perhaps the sudden chill warned off all the trollops. I can't say I miss them,” responded John. They walked quickly, for though it was still technically fall, the air was so thick and cold that their breath fogged out like a church censer whenever they spoke, and what's more, they were dressed in thin frockcoats, clothing not fit for winter weather. “Where are you up to in Coke, George?” asked Robert, as they neared the barracks at the end of the street, and George began “Well, I just commenced the sixth chapter, about Frankalmoigne, and have been learning the Statutes of Mortmain…” but he was interrupted by a band of men running down the road, jack-tars by the look of ‘em, hollering at the top of their lungs, “To arms! To arms, O citizens, the bloody banner’s raised! Ye brethren of Lady Liberty, hasten to the Fields!”

“What the devil,” cried Robert, as more men ran past with torches, but truth be told, the wrath fomenting a fortnight long left no room for wonder, they knew that it was now the hour to rise from sleep, for they had, alongside the rest of that uneasy society, solicitously awaited it, praying nonetheless that some timely miracle might defray the inevitable contest. They stood dumbstruck for a moment, watching men race past them, before the sonorous sound of bells filled the static air, bells echoing from the nearby belfry of St. Johns. George, suddenly alarmed, and remembering that proverb of Spenser, that where there is smoke there is oft fire, said, “Do you think it's a fire...” but Robert, barely heeding his words, began to walk quickly down the street, and the two followed after him. The nearer they got to the Fields, the more they could hear cacophonous yelling and nearing the corner on the Broadway, they looked out onto the grass lawn of the Fields opposite them.

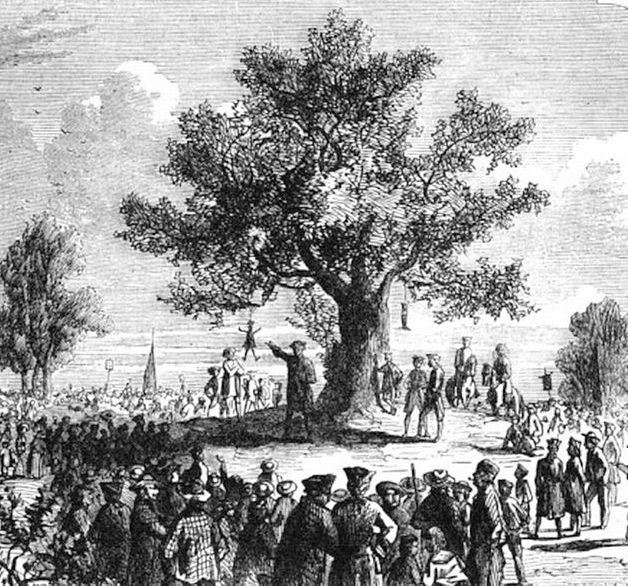

The Fields were a large public common wedged between the Broad Way and a new Presbyterian meetinghouse. The wide thoroughfare, hardly deviating its ancient course from the old foot-beat Wickquasgeck, a hunting path that wormed its way through a medieval grove, now girdled a fair lawn dotted with sparse trees. In the days of yore, before the herald of Christendom trumpeted the good news, this very lawn was the place of common sacrifice to the unnamed animistic deities, nay demons, haunting the forests in old America. In those wild days men in herbal-camouflage often stalked their antlered foe down the Broadway; now ambled past a carriage or two, here a rustic hansom, there a slow concourse of cattle. Then the field was also a place of penal execution, a true Akeldama of a field, and thus deep in the clay were mounds upon mounds of untimely Indian bone-stuff. Yet this evening upon this lawn stood a motley crowd of people (entirely unaware of the pallid masque enduring still beneath their feet) all joined together in seemingly one aim, as men in rustic garb stood kith and kin with dandies, all circling a sprawling antique elm. On its gnarled branches hung glass lanterns, shining light-beams of blue, red, and green down onto the voracious crowd. Freshly nailed on the bark of that tree, for amber sap dripped down like blood from the skin, was a sign writ in black paint, stating:

England's Folly

And America's Ruin

Beneath the roof of those tangled boughs stood a man upon an elevated platform, who dressed in the simplicity of a Quaker, but spoke with the veracity and strength of a lawyer. As the trio approached the elm, they noticed that swinging from the farthest stretching branch was a form of the governor in effigy, hanging by a noose, and a little behind that effigy was a form of the devil; the red demon of hell there swung conjoined in fate with the governor. George immediately winced at this blatant disregard for the government, and though he shared their sentiments, ‘twas the form not the matter than pricked his conscience. In short, he noticed that the crowd seemed to be inflamed and hell-bent upon making a demonstration.

“Spy them,” said Robert, “fresh from the tavern! True patriots these are, tripping over their dirty feet.” While this was true, for the putrid smell of ethanol, yeast, and sweat lingered in the chilly air, true as well was the fact that many men of prominence- lawyers, merchantmen, clergymen- or in a word, gentlemen, seemed to congregate among the rabble, and tainted the miasmatic tincture with a subtle hint of ambergris. Likewise, be not fooled pleasant, patient reader, for in some sense, the immediate disgust with which these three gentlemen beheld the present congregation, of such an unnatural mixing of breeding and learning into a common mass of boiling quasi-anarchy, there was, nevertheless, some latent pride at the intense jealousy with which their countrymen sought to preserve their liberties. Such it was, with a mixture of highborn disdain and philosophic pride, that those three immediately joined the crowd, lured on, one could suppose, by the same affective desire that brought many to that park, to see some sort of answer on behalf of the government regarding the present crisis.

Before they could gather their bearings any further, the man at the elm waved his arms, signaling silence to the mob, and began:

“Friends of Liberty! We gather here tonight under that most auspicious star, I speak of course of God almighty, who directs His providence throughout His works, directing us His people to fulfill His will. Moreover, what is His will, this I ask you all? ‘Tis a question spoke of in monasteries and by the millstone, and amid other answers is this: at least part of His will is that we maintain rightful government with laws reflecting the natural and Christian liberties of mankind, thus spake our sacred scriptures,” looking down quickly at a small bible he added, “for citation see the first verse of the 13th chapter of the Epistle of Paul to the Romans. Our Mother Country, Great Britain, may her strength never fade, has long guarded the constitution which safeguards these Heaven-vouched-for liberties, began by those righteous Saxons, and maintained by our great and honorable King George the Third, whom God preserve. Yet, by the evil works of evil ministers, or should I say, of evil Tories!” here the mob delightfully cackled, “Aye, by these evil works there is a concerted effort to usurp our rights and our liberties, which concerns every man in every station.

“The Stamp Act has inflamed the colonies, from one end of America to t’other, from the Massachusetts to Virginia, and we are not immune to the wholesale destruction of these ancient and venerable rights! That is why we are here, friends, for we are to march as one people with one voice and one mind to Fort George and will demand from the Governor that he put an end to the madness. We will demand that he refuse these foreign stamps, which have been so malignantly entrusted to his care, and that he will implore the Parliament to rescind this unconstitutional act, so help us God. Yet, before we begin our civic pilgrimage, let us join in song, and sing a hymn penned by a true patriot, Mr. Dickinson, the Farmer from Pennsylvania.”

And so the crowd began to sing a song crafted from the English tune “Hearts of Oak”, and George stood scatterbrained, for this melody, derived from the noble shores of England, evinced in his loyal mind the stories of the brave men of the Royal Navy upon the high seas, fighting courageously in oaken frigates for the very thing of which the crowd sang- for liberty:

“Come join in hand, brave Americans all,

And rouse your bold hearts at fair Liberty's call;

No tyrannous act shall suppress your just claim

Or stain with dishonor America's name.

In freedom we're born and in freedom we'll live,

Our purses are ready. Steady, friends, steady,

Not as slaves, but as freemen our money we'll give!”

Warning: The Yellow Cardinal contains adult themes that may not be suitable for all audiences under the age of 18. Some chapters may contain descriptions of graphic scenarios including but not limited to: suggestive materials, violence, 18th century racism and slavery, sexism, etc. Read with caution and/or parental permission.

Comments