Daniel Horsmanden

- Colonial-NewYorker

- Oct 8, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 19

Daniel Horsmanden, chief justice of the New York Court of Judicature, died in 1778 as an unpopular man[1]. He had presided over one of New York’s most infamous cases (the 1741 slave conspiracy), and pursued the deaths of countless men. Not only did he manage his workload with the zeal of an 18th century man of learning, he made an everlasting record of his doings in his 1744 Journal of Proceedings, albeit as the anonymous “Recorder of the City of New York”. Yet, while he was indeed hated for his support of the proceedings against the slaves in 1741, his reputation has indeed blackened much due to other factors.

Harvard scholar Jill Lepore notes that of the many actors involved in 1741, Horsmanden is the only lawyer missing from the modern streets of lower Manhattan; we have Chambers St, Murray St, Delancey St, yet, as Lepore points out, no Horsmanden Street. Horsmanden was not alone in the prosecution of the slaves, indeed, the entire bar association of colonial Manhattan helped in its furtherance.

There must be something further to his tarred reputation.

In 1776, in response to the Declaration of Independence, Lord Richard Howe issued a statement to the New York colonists, and in the November 4th edition of the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, Daniel Horsmanden was among a page full of subscribers who replied “bear[ing] our true allegiance, to our rightful Sovereign George the Third, as well as warm affection to his sacred person, crown and dignity”.

Yet, biography as well as public memory is anachronistic and backwards looking, and indeed, had Washington failed in his retreat from Brooklyn the previous autumn, and had Congress lost the War of Independence, perhaps history would look less unkindly upon Horsmanden’s declaration of loyalty. Nevertheless, the victors write the tale, so the saying goes, and the rest is history.

However, a decade before 1776, Horsmanden had engaged in yet another infamous trial, that of King vs. William Prendergast of 1766[2]. He sat on the bench to hear the testimony against a man who, it was alleged, had committed high treason. In 1765, amid the violent protests against the Stamp Act, Hudson Valley tenants were uprising against their manorial lords. Prendergast, it was alleged, had been one of many leaders in a ring of country “levelers”, and had waged war against New York Province.

Before we get into that, however, we should define treason. In the colonial period, treason was divided into high and petit treason, and high treason was itself divided into six types, according to the English Jurist Sir Edward Coke[3]. The class of treason that William Prendergast was accused of was of the third, “levying war against the King.”

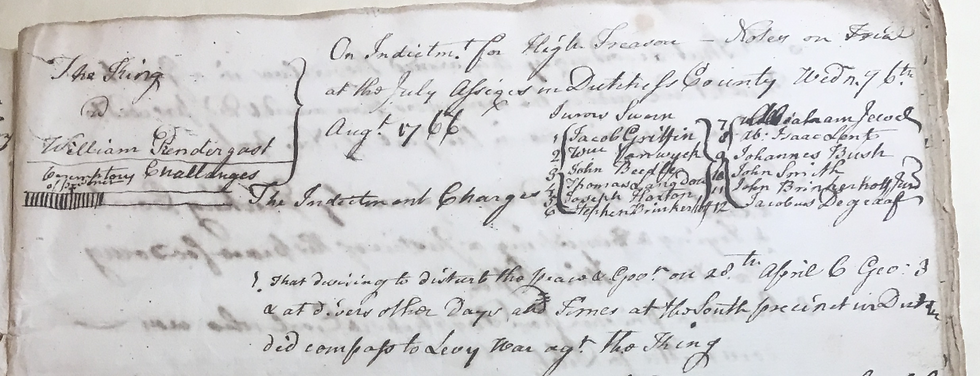

As far as the history of Horsmanden’s involvement in this trial, the judicial record, unlike that of the 1741 conspiracy, is oddly silent. The only official record of the trial that remains is the trial notes of a court clerk found in a box of Dutchess County records housed by the New York Historical Society. The record begins, “On indictment for High Treason- Notes on Trial and the July Assizes in Dutchess County, 1766” and lists the indictment and further, more than 15 witnesses for the Crown.

Certainly, the document has a prosecutor’s bias, and ignores much of the defense. Yet, the taciturnity of the defense could rather be due to, as it was written in the September 4th, 1766 New York Gazette and Weekly Post Boy, the fact that the prisoner (Prendergast) “came to make his [own] defense.” Not only did he make his own defense, but further, in that autumnal newspaper an odd story was reported about his wife, who had aided him in his defense, and is worth mentioning in full:

“[her behavior] occasioned one of the Council for the King to make a Motion to move her out of Court, lest she might too much influence the Jury…[that] her Looks might too much affect the Jury- He [the prosecutor] was answer’d, that for the same Reason, he might as well move that the Prisoner himself should be cover’d with a Veil, lest the Distress Painted in his Countenance should too powerfully excite Compassion.”.

This colorful account is supplemented by a note written in contemporary handwriting found on the NYHS copy of the Gazette, which reads:

“I attended this Trial as Council for the King. The Account...[of] the motion to have the Prisoners wife [illegible, though likely “whisked”] out of court were absolute Falsehoods. Nothing happened in Court to give the least Room for my part of what I have read- and the whole account of the Behavior of the prisoner was certainly exaggerated.”

It is indicative of this discrepancy of information that the case itself might have been highly controversial at a time of great controversy.

In the end, the court at Poughkeepsie ruled that Prendergast was guilty, and as such, they issued a barbaric punishment, not far beyond what was normal fare at the English Common Law, and further, as we have seen from the 1741 proceedings, not abnormal for the jurists of colonial NY:

“In accordance thereof, we deem that the prisoner be led back to the place whence he came and from thence shall be drawn on a hurdle to the place for execution, and then shall be hanged by the neck, and then shall be cut down alive, and his entrails and privy members shall be cut from his body, and shall be burned in his sight, and his head shall be cut off, and his body shall be divided into four parts, and shall be disposed of at the king's pleasure.”

Yet, Prendergast’s wife, Mehitable Wing, issued a petition to the royal governor, Sir Henry Moore, for the King’s clemency, and it was granted, and Prendergast lived out his days as a New York farmer. Whether Horsmanden had as great an influence in the judgement of the court in 1766 as he did in 1741 is unclear.

Overall, Horsmanden had a convoluted history of being a part of historically significant legal cases, yet being, as the phrase goes nowadays, on the wrong side of history. He was in 1741, 1766, and in 1776, and thus he died without fame or fortune, for his country had forsaken him. For pie’s sake, even his Journal of the Proceedings failed to sell out in 1744! It seems the odds were stacked against him.*

[1] For more on Horsmanden’s life and death, inasmuch as it related to the 1741 Slave Conspiracy, read Jill Lepore’s New York Burning.

[2] For more on the 1766 Tenant Uprisings, read Irving Mark. Agrarian Revolt in Colonial New York, 1766. 1 American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 111 (1942).

[3] Third Institute of the Lawes of England, Concerning High Treason, and other Pleas of the Crown and Criminal Causes.

*This article is one in a series exploring the #1741slaveconspiracy, last discussed here: https://www.newyorkhistories.com/blog/spanish-what

Comments